Post by Purple Pain on Aug 28, 2020 15:13:38 GMT -6

What do rookie performances say about the future?

...

...

www.pff.com/news/nfl-how-important-is-rookie-performance-when-it-comes-to-predicting-career-performance

Let me know if there are any other position groups you're curious about. I'll gladly copy and paste for you to see.

As a part of our pre-draft coverage, I wrote an article that looked at rookie performance and learned that the step from college to the NFL comes with a steep learning curve. I discovered that first-year players struggle not only when it comes to earning playing time but also when it comes to performing at a high level when they are on the field; we also learned that there are differences across positions, with linemen generally having the hardest acclimation period while running backs are mostly ready on Day 1.

So, it isn’t the end of the world if a first-year player gets off to a bad start, as bad rookies are supposed to improve, but it doesn't necessarily mean that this disappointing first year is meaningless. If Player X has a better rookie season than Player Y, we would expect both to improve in Year 2, but how confident can we be that Player X will keep the edge and have a better career? And how much does the prior from draft status still matter after the rookie season?

We at PFF take great pride in grading and charting every player on every play of every game — a necessary process in a sport in which sample size is king. Because of this, it’s fairly obvious that the combined performance after two years is more predictive toward future performance than just the rookie year. But, what if we keep the sample size the same?

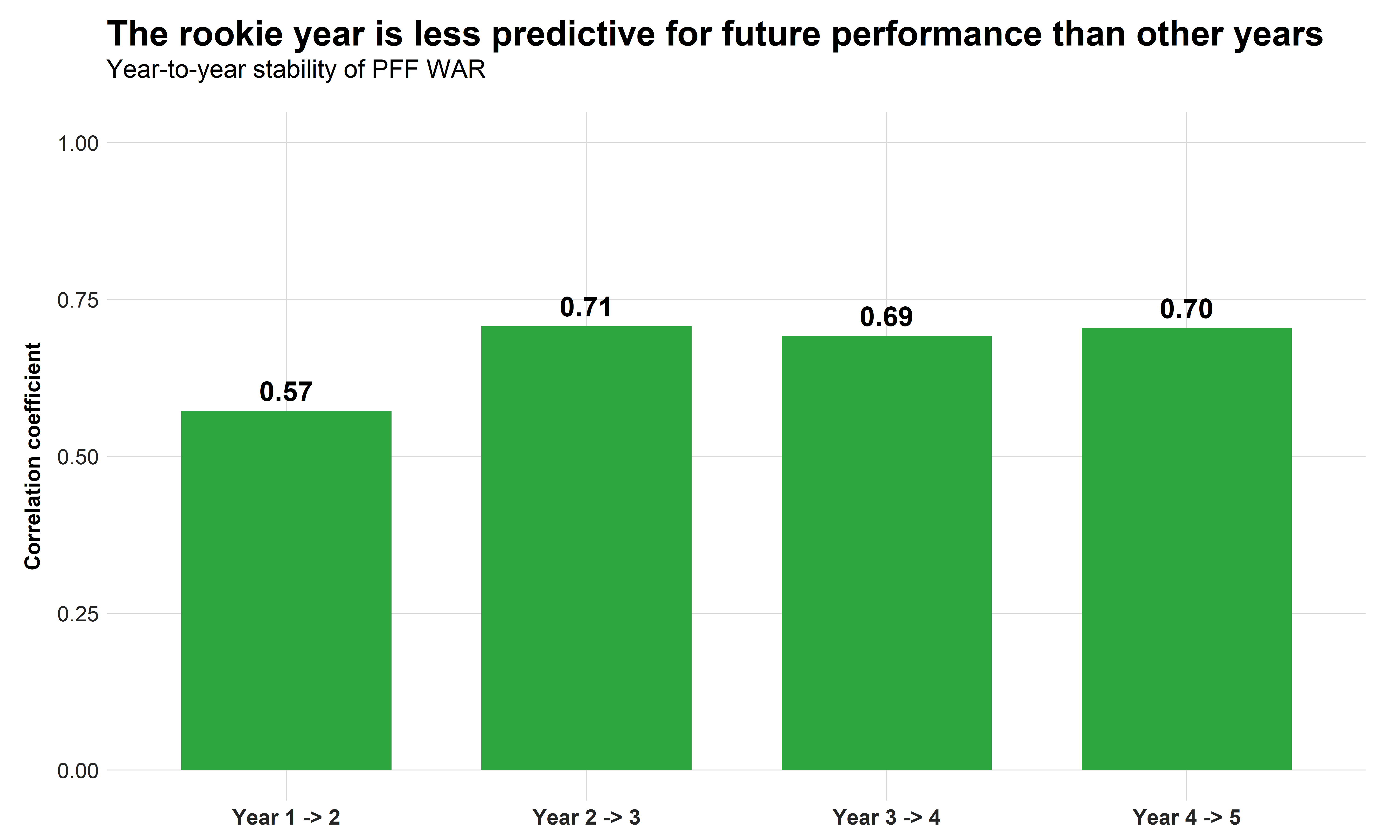

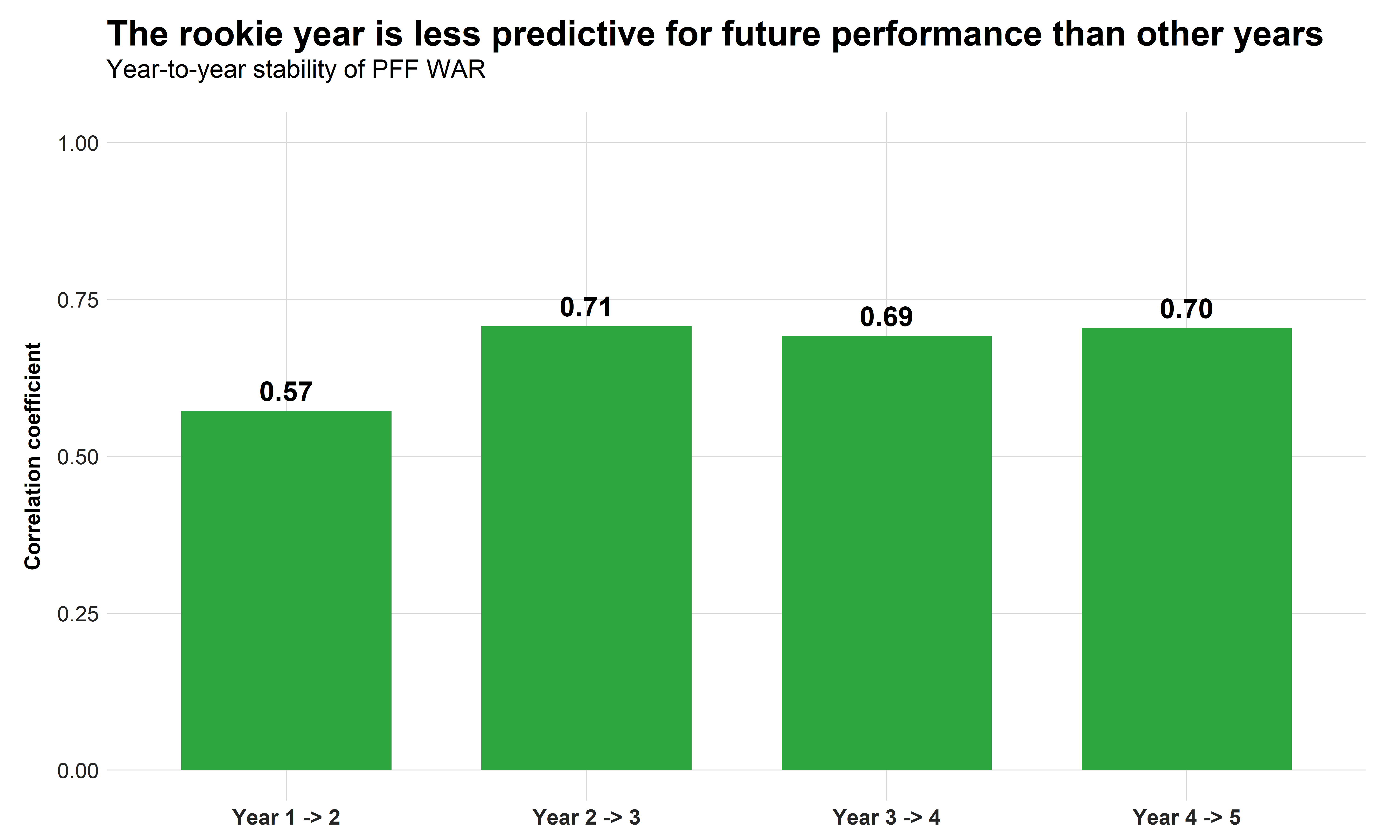

The following chart shows the year-to-year R-squared values of PFF Wins Above Replacement (WAR) of NFL players with different levels of experience.

We notice that the rookie year is indeed less predictive than the following years as it pertains to next-year performance. In particular, when forecasting a player going into Year 3, we should weigh the second year higher, especially when there is a large discrepancy between Year 1 and Year 2 performance.

To gain even more insight, we can perform a more nuanced analysis for each position group. Since there doesn’t seem to be a difference in the inherent predictive power of Year 2 through Year 4 when it comes to predicting the next year, we compare the correlation between WAR in the first and second year to year-to-year correlation when going from Years 2,3 and 4 to Years 3,4 and 5.

To get a feeling for the uncertainty of our analysis, we bootstrap 1,000 times from a 50% sample of all players of a given position. This means that for, say, wide receivers, we will randomly select half of all wide receivers drafted between 2005 and 2015 and then compute:

- The correlation between WAR in the first and second year

- The correlation between WAR in the first and second year when we also use draft status as a predictor

- The year-to-year correlation when going from Years 2,3 and 4 to Years 3,4 and 5

- The year-to-year correlation when going from Years 2,3 and 4 to Years 3,4 and 5 when we also use draft status as a predictor

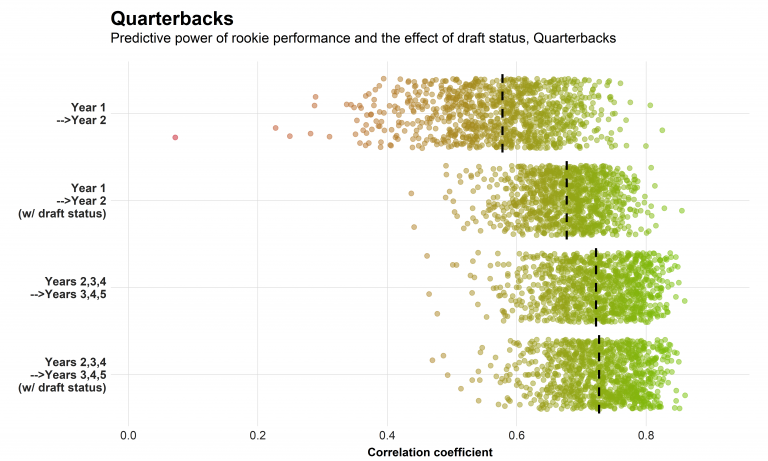

We iterate this process 1,000 times and visualize all 4,000 computed correlation coefficients in a chart. The mean correlation coefficients are visualized with a dashed line, and the width of the distribution can be considered as a measurement of how certain we are that we would find the same mean correlations when performing the same analysis for players who joined the NFL via the draft classes of 2016 through 2025.

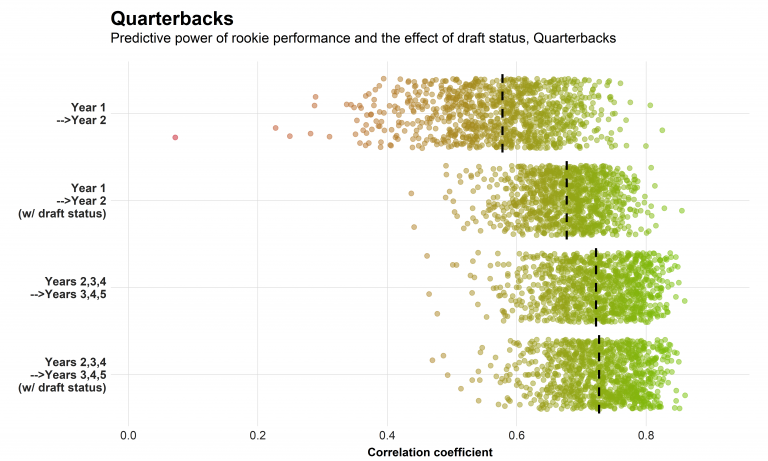

QUARTERBACKS

For quarterbacks, we find that rookie performance is less predictive than performance in later years and that draft status still plays a huge role when projecting QBs going into Year 2.

We incorporated these results when we projected all starting quarterbacks going into 2020, and this explains why Gardner Minshew projects lower than both Daniel Jones and Dwayne Haskins, even though Minshew outperformed both in terms of PFF passing grade and expected points added per play in 2019.

However, we also see that draft status loses its importance toward predicting future performance after Year 2, after which we can tell much more about a quarterback than we can after his rookie year.

My colleague Kevin Cole touched on this subject in an article about the rarity of third-year breakouts: After Year 2, we have a pretty good idea about who a QB is, and if he hasn’t shown at least average play on a fairly consistent basis, the chances for a later breakout are small.

Staying with the 2019 draft class, this means that if Minshew outplays Haskins and Jones once more, we would be running out of reasons to project the latter two as better quarterbacks going forward.

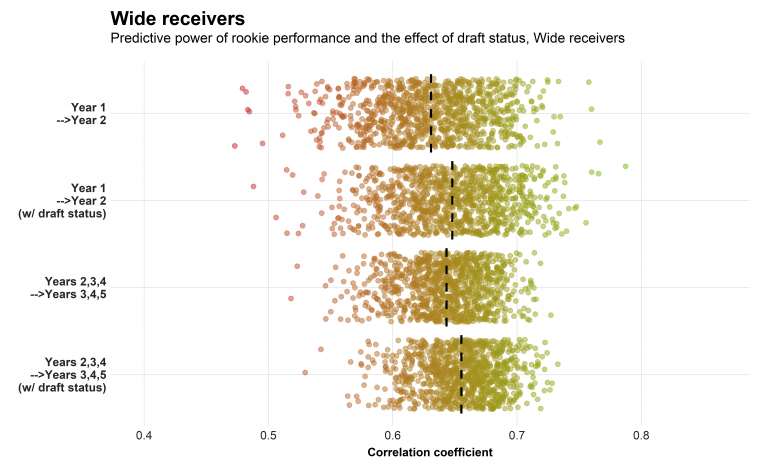

OFFENSIVE SKILL PLAYERS

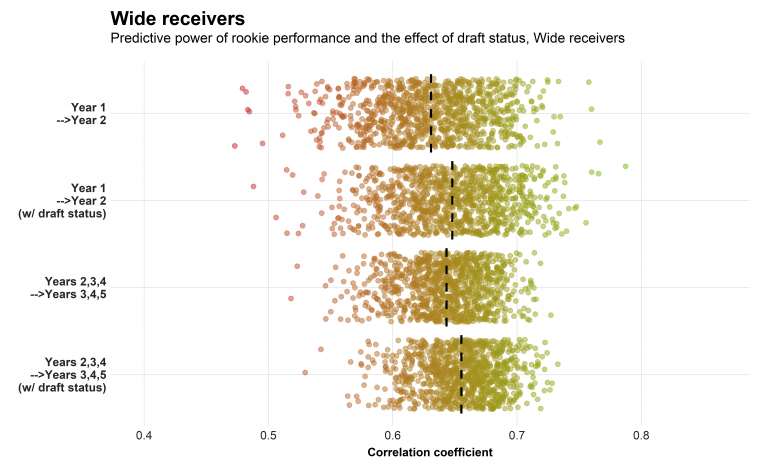

Things start to look a little different for wide receivers, as the predictive power of the rookie year isn’t much weaker than that for later years, and draft status doesn’t play a huge role even when going into Year 2.

Furthermore, the correlation coefficient of 0.63 even without using draft status is the highest among all positions. This finding is anecdotally supported by the following list of all rookie wide receivers of the last decade who played at least 200 snaps and earned a receiving grade of 75.0 or better:

Rookie performance being most predictive for wide receivers is certainly very good news for the careers of A.J. Brown and Terry McLaurin, and the fact that draft status plays only a very minor role after the rookie season is good news for Hunter Renfrow but bad news for receivers like N’Keal Harry or J.J. Arcega-Whiteside.

While there is still a chance the latter two players become good NFL receivers, we should neither over-rely on their draft status nor overestimate the true probability of this happening.

So, it isn’t the end of the world if a first-year player gets off to a bad start, as bad rookies are supposed to improve, but it doesn't necessarily mean that this disappointing first year is meaningless. If Player X has a better rookie season than Player Y, we would expect both to improve in Year 2, but how confident can we be that Player X will keep the edge and have a better career? And how much does the prior from draft status still matter after the rookie season?

We at PFF take great pride in grading and charting every player on every play of every game — a necessary process in a sport in which sample size is king. Because of this, it’s fairly obvious that the combined performance after two years is more predictive toward future performance than just the rookie year. But, what if we keep the sample size the same?

The following chart shows the year-to-year R-squared values of PFF Wins Above Replacement (WAR) of NFL players with different levels of experience.

We notice that the rookie year is indeed less predictive than the following years as it pertains to next-year performance. In particular, when forecasting a player going into Year 3, we should weigh the second year higher, especially when there is a large discrepancy between Year 1 and Year 2 performance.

To gain even more insight, we can perform a more nuanced analysis for each position group. Since there doesn’t seem to be a difference in the inherent predictive power of Year 2 through Year 4 when it comes to predicting the next year, we compare the correlation between WAR in the first and second year to year-to-year correlation when going from Years 2,3 and 4 to Years 3,4 and 5.

To get a feeling for the uncertainty of our analysis, we bootstrap 1,000 times from a 50% sample of all players of a given position. This means that for, say, wide receivers, we will randomly select half of all wide receivers drafted between 2005 and 2015 and then compute:

- The correlation between WAR in the first and second year

- The correlation between WAR in the first and second year when we also use draft status as a predictor

- The year-to-year correlation when going from Years 2,3 and 4 to Years 3,4 and 5

- The year-to-year correlation when going from Years 2,3 and 4 to Years 3,4 and 5 when we also use draft status as a predictor

We iterate this process 1,000 times and visualize all 4,000 computed correlation coefficients in a chart. The mean correlation coefficients are visualized with a dashed line, and the width of the distribution can be considered as a measurement of how certain we are that we would find the same mean correlations when performing the same analysis for players who joined the NFL via the draft classes of 2016 through 2025.

QUARTERBACKS

For quarterbacks, we find that rookie performance is less predictive than performance in later years and that draft status still plays a huge role when projecting QBs going into Year 2.

We incorporated these results when we projected all starting quarterbacks going into 2020, and this explains why Gardner Minshew projects lower than both Daniel Jones and Dwayne Haskins, even though Minshew outperformed both in terms of PFF passing grade and expected points added per play in 2019.

However, we also see that draft status loses its importance toward predicting future performance after Year 2, after which we can tell much more about a quarterback than we can after his rookie year.

My colleague Kevin Cole touched on this subject in an article about the rarity of third-year breakouts: After Year 2, we have a pretty good idea about who a QB is, and if he hasn’t shown at least average play on a fairly consistent basis, the chances for a later breakout are small.

Staying with the 2019 draft class, this means that if Minshew outplays Haskins and Jones once more, we would be running out of reasons to project the latter two as better quarterbacks going forward.

OFFENSIVE SKILL PLAYERS

Things start to look a little different for wide receivers, as the predictive power of the rookie year isn’t much weaker than that for later years, and draft status doesn’t play a huge role even when going into Year 2.

Furthermore, the correlation coefficient of 0.63 even without using draft status is the highest among all positions. This finding is anecdotally supported by the following list of all rookie wide receivers of the last decade who played at least 200 snaps and earned a receiving grade of 75.0 or better:

Rookie performance being most predictive for wide receivers is certainly very good news for the careers of A.J. Brown and Terry McLaurin, and the fact that draft status plays only a very minor role after the rookie season is good news for Hunter Renfrow but bad news for receivers like N’Keal Harry or J.J. Arcega-Whiteside.

While there is still a chance the latter two players become good NFL receivers, we should neither over-rely on their draft status nor overestimate the true probability of this happening.

OFFENSIVE LINEMEN

There is a large gap between the predictive power of rookie seasons and later seasons for offensive tackles, but interestingly, we can overcome this gap by incorporating draft status in our projections.

This is certainly very good news for Andre Dillard, whose 59.2 pass-blocking grade as a rookie was rather disappointing, but given his draft status and the fact he played fewer than 200 pass-blocking snaps, his career projection doesn’t look any worse than it did at this point last year.

Just as it is for offensive tackles, we should wait until after Year 2 to be confident in our assessments about interior offensive linemen. There is a difference, though: As we already established in an earlier article, draft status carries less predictive power for interior linemen, and that’s apparently true even after the rookie year.

Just as it is for offensive tackles, we should wait until after Year 2 to be confident in our assessments about interior offensive linemen. There is a difference, though: As we already established in an earlier article, draft status carries less predictive power for interior linemen, and that’s apparently true even after the rookie year.

There is a large gap between the predictive power of rookie seasons and later seasons for offensive tackles, but interestingly, we can overcome this gap by incorporating draft status in our projections.

This is certainly very good news for Andre Dillard, whose 59.2 pass-blocking grade as a rookie was rather disappointing, but given his draft status and the fact he played fewer than 200 pass-blocking snaps, his career projection doesn’t look any worse than it did at this point last year.

Just as it is for offensive tackles, we should wait until after Year 2 to be confident in our assessments about interior offensive linemen. There is a difference, though: As we already established in an earlier article, draft status carries less predictive power for interior linemen, and that’s apparently true even after the rookie year.

Just as it is for offensive tackles, we should wait until after Year 2 to be confident in our assessments about interior offensive linemen. There is a difference, though: As we already established in an earlier article, draft status carries less predictive power for interior linemen, and that’s apparently true even after the rookie year.

The percentages are not very high, but there is more hope for safeties, edge defenders and offensive tackles. According to our findings above, one has to adjust these percentages for highly drafted players for some positions. For example, the percentage should be higher for first-round cornerbacks but not much higher for wide receivers.

Bringing everything together, the chances that N’Keal Harry or J.J. Arcega-Whiteside will develop into good NFL wide receivers don’t seem to be much higher than 20% at this point.

Bringing everything together, the chances that N’Keal Harry or J.J. Arcega-Whiteside will develop into good NFL wide receivers don’t seem to be much higher than 20% at this point.

www.pff.com/news/nfl-how-important-is-rookie-performance-when-it-comes-to-predicting-career-performance

Let me know if there are any other position groups you're curious about. I'll gladly copy and paste for you to see.