Post by Funkytown on Aug 28, 2023 19:48:56 GMT -6

Reps matter, first of all. The trade up for Lance was always insane. Potential is fun and all, but NFL QB on-the-job training isn't always a great idea with someone so inexperienced. Also, if you aren't in a position to pick early in the first, maybe just ... find your Purdy! Vikes, maybe learn from San Fran! Maybe.

Some recent pieces exploring QBOTF:

Should Anthony Richardson’s inexperience concern NFL teams? History and Trent Dilfer say yes by Chris Vannini

“The No. 1 indicator of draft status is snaps played in college football,” Dilfer said. “When I did the draft, that’s the thing I’d always say on Day 2 after (fellow analyst Jon) Gruden. It ain’t how many starts he had in high school, what college or conference he’s at. It’s not the TV ratings. It’s how many snaps he played at a high level in college football.”

In search of context for Richardson’s shortage of starting experience, The Athletic examined the college careers of every first-round quarterback over the last 15 years. Richardson’s 13 career college starts are tied with Mitch Trubisky (the No. 2 pick in 2017) for the fewest in that span. (Young had 27; Stroud and Levis had 25.)

Since the 2008 draft, seven quarterbacks have been drafted in the first round with fewer than 20 collegiate starts. That technically includes Ryan Tannehill, who started as a wide receiver at Texas A&M before switching to quarterback.

Of the six full-time QBs, only Kyler Murray, who won a Heisman Trophy at Oklahoma, has put together true Pro Bowl-caliber production. The jury is still out on younger players such as Mac Jones and Trey Lance (and Lance would’ve started another season at North Dakota State if not for the pandemic moving the FCS season to the spring of 2021). Dilfer had a close relationship with Trubisky through Elite 11 and advised the quarterback to stay another year at North Carolina.

“I’m like, ‘Mitch, permission to speak freely? You know how much I think of you, had you at the Elite 11, think you’re a great player, one of your biggest fans. You’re not ready,’” Dilfer recalled. “’I know that sucks to hear. But do you want a few million now or hundreds of millions later? That’s what you have to wrestle with. My gut is you’ll get your first contract, and I don’t know if you’ll get a second contract because you haven’t faced enough live bullets, haven’t figured out who you are as a player or a person.’”

Trubisky was selected No. 2 overall in 2017 and took the Bears to the playoffs twice, but he wasn’t re-signed after the 2020 season. He went to the Buffalo Bills and then Pittsburgh Steelers as a backup, starting five games as an injury replacement last year.

“He did not like to hear it, and he did not listen to me,” Dilfer said. “But I’m almost 100 percent on these guys who are calling me beforehand.”

Since the 2008 draft, seven quarterbacks have been drafted in the first round with fewer than 20 collegiate starts. That technically includes Ryan Tannehill, who started as a wide receiver at Texas A&M before switching to quarterback.

Of the six full-time QBs, only Kyler Murray, who won a Heisman Trophy at Oklahoma, has put together true Pro Bowl-caliber production. The jury is still out on younger players such as Mac Jones and Trey Lance (and Lance would’ve started another season at North Dakota State if not for the pandemic moving the FCS season to the spring of 2021). Dilfer had a close relationship with Trubisky through Elite 11 and advised the quarterback to stay another year at North Carolina.

“I’m like, ‘Mitch, permission to speak freely? You know how much I think of you, had you at the Elite 11, think you’re a great player, one of your biggest fans. You’re not ready,’” Dilfer recalled. “’I know that sucks to hear. But do you want a few million now or hundreds of millions later? That’s what you have to wrestle with. My gut is you’ll get your first contract, and I don’t know if you’ll get a second contract because you haven’t faced enough live bullets, haven’t figured out who you are as a player or a person.’”

Trubisky was selected No. 2 overall in 2017 and took the Bears to the playoffs twice, but he wasn’t re-signed after the 2020 season. He went to the Buffalo Bills and then Pittsburgh Steelers as a backup, starting five games as an injury replacement last year.

“He did not like to hear it, and he did not listen to me,” Dilfer said. “But I’m almost 100 percent on these guys who are calling me beforehand.”

Early in his career as analyst, Dilfer said he would take Mark Sanchez No. 1 overall in 2009, ahead of the eventual No. 1 pick Matthew Stafford. Sanchez, who entered the NFL with just 16 career college starts, did have early success with the New York Jets and reached the AFC Championship Game twice, but the bottom fell out and he spent 2014 through 2018 with four different teams before retiring.

“I was wrong on Sanchez because of the amount of snaps played,” Dilfer said. “Where I whiffed, that was before I understood about the amount of time being a quarterback.”

What Dilfer means by “being a quarterback” is more than snaps and starts. It’s about QB moments, as he defines it.

“It’s meetings, locker room dynamics, media, fan engagement, being booed and being cheered,” Dilfer said. “Being the quarterback has the biggest burden of any player. If you don’t have a lot of reps of being the quarterback and all that entails, it can overwhelm you when it’s your profession.”

It’s why Dilfer believes this quarterback class could have some gems later in the draft in players like Fresno State’s Jake Haener and Purdue’s Aidan O’Connell. Physical ability determines who gets picked at the top of the draft, but Dilfer puts value on the college experience of someone like Haener.

“I was wrong on Sanchez because of the amount of snaps played,” Dilfer said. “Where I whiffed, that was before I understood about the amount of time being a quarterback.”

What Dilfer means by “being a quarterback” is more than snaps and starts. It’s about QB moments, as he defines it.

“It’s meetings, locker room dynamics, media, fan engagement, being booed and being cheered,” Dilfer said. “Being the quarterback has the biggest burden of any player. If you don’t have a lot of reps of being the quarterback and all that entails, it can overwhelm you when it’s your profession.”

It’s why Dilfer believes this quarterback class could have some gems later in the draft in players like Fresno State’s Jake Haener and Purdue’s Aidan O’Connell. Physical ability determines who gets picked at the top of the draft, but Dilfer puts value on the college experience of someone like Haener.

theathletic.com/4451278/2023/04/26/nfl-draft-anthony-richardson-trent-dilfer/

Building the perfect NFL QB: Meet the mysterious private coaches on the cutting edge by Alec Lewis

The future of the Indianapolis Colts takes his shirt off and walks toward a chain-link fence. “Do a few of these?” Anthony Richardson asks. A man standing nearby nods, so Richardson grabs a harness that is connected to the fence by a thick, elastic band. Richardson straps the harness around his waist. The band tightens. Constrained by the contraption, Richardson rotates his hips. “Arghhh,” he grunts. It all looks so unconventional.

“Should I do more?” Richardson asks after a while.

The man standing nearby shakes his head.

“No, you’re good,” the man says. “But come over here.”

This is all unfolding on a soccer field in northern Florida surrounded by pine trees in the midst of an “excessive heat warning.” Cicadas buzz. Pickleballs dink off paddles on a nearby court. It’s late July, and training camp is on the horizon, so Richardson, selected fourth by the Colts in the 2023 draft, is putting the final touches on his preseason preparation.

He disconnects from the fence and heads over toward a cement wall. The man hands him a mint-green ball that weighs more than a football and has the feel of a lacrosse ball.

“Now, do a few of these,” the man says, raising the ball above his head, moving his body fluidly, then launching it at the wall.

Without hesitation, Richardson mimics the drill. He acts like this entire process is normal — a high-profile quarterback warming up to throw with strategic body movements and custom-tailored weighted-ball exercises — and that’s because he believes. He is convinced that to fulfill his ultimate potential as a quarterback in the National Football League, in order to reach his ceiling, he should be listening to the man who designed these exercises — even though this man didn’t play football past high school.

And Richardson is not alone.

“The first time I met him, I walked away from that conversation thinking, ‘This guy understands it better than anyone right now,’” Tampa Bay Buccaneers quarterback John Wolford says.

Brock Purdy, who is expected to be the San Francisco 49ers’ starting quarterback this season, adds, “Leaving college and going to the NFL, I needed to develop into a real, true professional quarterback, and those guys (in Florida) did that for me.”

The man they trust — the man standing nearby — is Dr. Tom Gormely, and he is the director of sports performance and head of sports science at Tork Sports Performance. His background is mostly in physical therapy and he has researched how athletes generate force, power and velocity.

Gormely works in tandem with Will Hewlett, who orchestrates the on-field training. Hewlett did play quarterback in college, but even he is the antithesis of a traditionalist. Before his nearly two decades of experience training quarterbacks, Hewlett grew up in Australia. He entered the QB development space after a random conversation with a work colleague at a Ford dealership.

“The day I said, ‘I think I’m going to train quarterbacks,’ my high school coach said, ‘No offense, Will, but who the hell is Will Hewlett and why the hell would anyone want to train with you?’” Hewlett says.

So, how the hell did we get here? To a place where NFL quarterbacks such as Richardson, Purdy, Wolford and many others are adamant about the benefits of a new approach assembled so far from the football establishment? The answer is both absurdly complex and jarringly simple. It is a decades-long lesson on ego and evolution, technology and change. It is also a tale with vast implications that contextualizes the development of players such as Josh Allen and Jalen Hurts.

And if all of that sounds a bit out there, that’s because so much of this is at the moment — in football, at least.

“Should I do more?” Richardson asks after a while.

The man standing nearby shakes his head.

“No, you’re good,” the man says. “But come over here.”

This is all unfolding on a soccer field in northern Florida surrounded by pine trees in the midst of an “excessive heat warning.” Cicadas buzz. Pickleballs dink off paddles on a nearby court. It’s late July, and training camp is on the horizon, so Richardson, selected fourth by the Colts in the 2023 draft, is putting the final touches on his preseason preparation.

He disconnects from the fence and heads over toward a cement wall. The man hands him a mint-green ball that weighs more than a football and has the feel of a lacrosse ball.

“Now, do a few of these,” the man says, raising the ball above his head, moving his body fluidly, then launching it at the wall.

Without hesitation, Richardson mimics the drill. He acts like this entire process is normal — a high-profile quarterback warming up to throw with strategic body movements and custom-tailored weighted-ball exercises — and that’s because he believes. He is convinced that to fulfill his ultimate potential as a quarterback in the National Football League, in order to reach his ceiling, he should be listening to the man who designed these exercises — even though this man didn’t play football past high school.

And Richardson is not alone.

“The first time I met him, I walked away from that conversation thinking, ‘This guy understands it better than anyone right now,’” Tampa Bay Buccaneers quarterback John Wolford says.

Brock Purdy, who is expected to be the San Francisco 49ers’ starting quarterback this season, adds, “Leaving college and going to the NFL, I needed to develop into a real, true professional quarterback, and those guys (in Florida) did that for me.”

The man they trust — the man standing nearby — is Dr. Tom Gormely, and he is the director of sports performance and head of sports science at Tork Sports Performance. His background is mostly in physical therapy and he has researched how athletes generate force, power and velocity.

Gormely works in tandem with Will Hewlett, who orchestrates the on-field training. Hewlett did play quarterback in college, but even he is the antithesis of a traditionalist. Before his nearly two decades of experience training quarterbacks, Hewlett grew up in Australia. He entered the QB development space after a random conversation with a work colleague at a Ford dealership.

“The day I said, ‘I think I’m going to train quarterbacks,’ my high school coach said, ‘No offense, Will, but who the hell is Will Hewlett and why the hell would anyone want to train with you?’” Hewlett says.

So, how the hell did we get here? To a place where NFL quarterbacks such as Richardson, Purdy, Wolford and many others are adamant about the benefits of a new approach assembled so far from the football establishment? The answer is both absurdly complex and jarringly simple. It is a decades-long lesson on ego and evolution, technology and change. It is also a tale with vast implications that contextualizes the development of players such as Josh Allen and Jalen Hurts.

And if all of that sounds a bit out there, that’s because so much of this is at the moment — in football, at least.

Some things are obvious. This offseason, for example, one NFL team reached out to Kyle Boddy, the founder of Driveline Baseball. The team invited Boddy to pitch the decision-makers on how he would help their quarterback throw harder. Minutes after his presentation, they said: “OK, we’re in. How much does it cost?” Another NFL team is already thinking about how biomechanical analysis may help to position its pass rushers in spots that are more suitable for their body’s movement profile.

Progress is happening outside the NFL, too. Wolford and Gormely are trying to develop an iPhone application that democratizes biomechanical analysis and schematic evaluation for quarterbacks at all levels. Greg Rose, the owner of the Titleist Performance Institute, is in the process of developing a certification for quarterback coaches built around optimizing ground force and rotational velocity. Dub Maddox, a six-time state championship-winning high school football coach in Oklahoma who, not coincidentally, learned from Darin Slack at the same time as Hewlett, is using virtual reality to increase the number of reps a quarterback can get away from the field.

“If I could bet on the long-term stock market of QB play,” Wolford says, “I’d be wheeling and dealing trying to invest in that.”

O’Sullivan thinks the trajectory of coaching transcends the NFL space. He recently attended the Elite 11 camp and was blown away by the high school talent.

“There are so many more guys that I would classify as polished,” he says.

Progress is happening outside the NFL, too. Wolford and Gormely are trying to develop an iPhone application that democratizes biomechanical analysis and schematic evaluation for quarterbacks at all levels. Greg Rose, the owner of the Titleist Performance Institute, is in the process of developing a certification for quarterback coaches built around optimizing ground force and rotational velocity. Dub Maddox, a six-time state championship-winning high school football coach in Oklahoma who, not coincidentally, learned from Darin Slack at the same time as Hewlett, is using virtual reality to increase the number of reps a quarterback can get away from the field.

“If I could bet on the long-term stock market of QB play,” Wolford says, “I’d be wheeling and dealing trying to invest in that.”

O’Sullivan thinks the trajectory of coaching transcends the NFL space. He recently attended the Elite 11 camp and was blown away by the high school talent.

“There are so many more guys that I would classify as polished,” he says.

Link:

theathletic.com/4730027/2023/08/01/quarterback-development-performance-tom-gormley/

PFF: Components of QB play and what they teach us about development at the position by Judah Fortgang

• This article serves as an introduction to future work on quarterback traits and development.

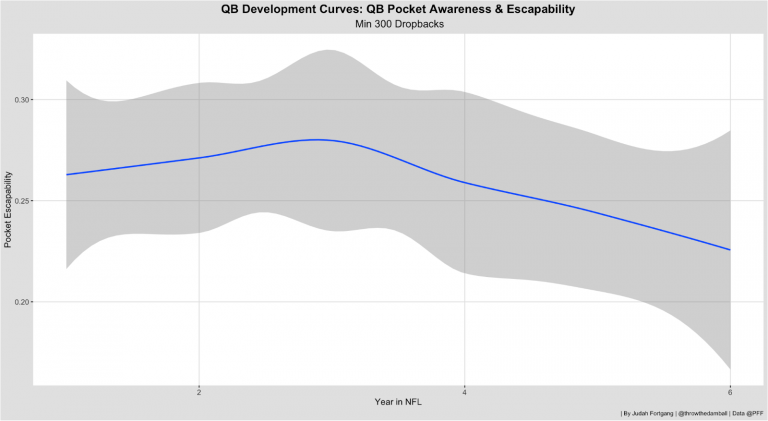

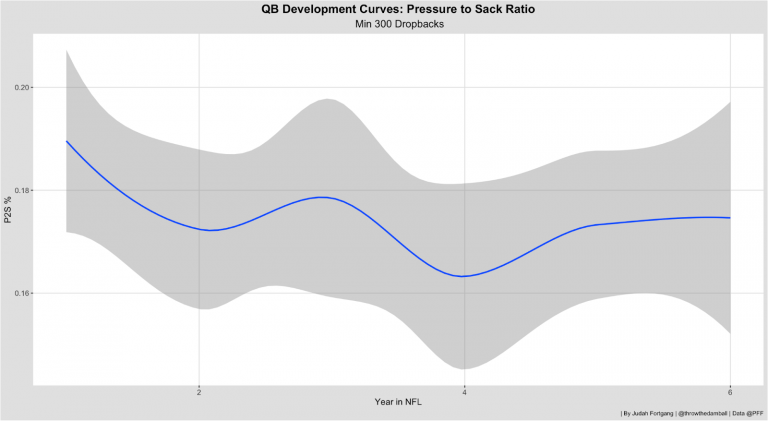

• Where QBs tend to improve over time: Young signal-callers get better in EPA and PFF WAR and throw into open windows more often as they gain NFL experience. However, quarterbacks don't seem to improve in pocket awareness and sack avoidance.

• Better understanding the trade-offs of QB play: For example, pressure on Jalen Hurts in 2022 led to a higher sack rate than in previous years, but he was staying in the pocket longer and delivering better and more frequent throws to open windows.

Quarterback is the most complex and important position in team sports. It makes sense, then, that it's also a position we try to understand as best as humanly possible through articles and metrics that evaluate performance and production.

This series of articles will take a slightly different route: Using PFF’s quarterback charting data as a foundation, we will explore the components of quarterback play — rhythm, accuracy, throw selection, progressions, decision-making and much more.

Through this exploration, we can hopefully learn more about the unique styles and skills of individual quarterbacks and the areas of the game and contexts in which they are more or less likely to succeed or fail. We can then apply those findings to better understand how components of quarterback skill sets interact with other players — for example, which quarterbacks would benefit from a good offensive line more than others? Which quarterback traits would best match with a dynamic after-the-catch receiver?

Lastly, by isolating specific traits, we can hopefully zero in on players whose traits allow them to deviate from the norm — for example, while quarterback play from a non-clean pocket is generally unstable, certain players, because of their traits, should be seen as outliers as opposed to noise.

This article will set the stage for an upcoming series on quarterback composites by focusing on, and answering, the following question: Which components of a quarterback's development lead to improvement? Put differently, we know that a quarterback is likely to increase their production from their first few NFL seasons to their next few seasons, but what part of their game develops the most?

Without looking at a signal-caller's production in specific areas (e.g., their expected points added across different situations such as play action or pressure), we will try to isolate broader attributes that lead to improved quarterback play. Do quarterbacks become more accurate? Improve their rhythm and timing? Improve their throw selection? Get better with progressions? Advance in their pocket awareness and escapability?

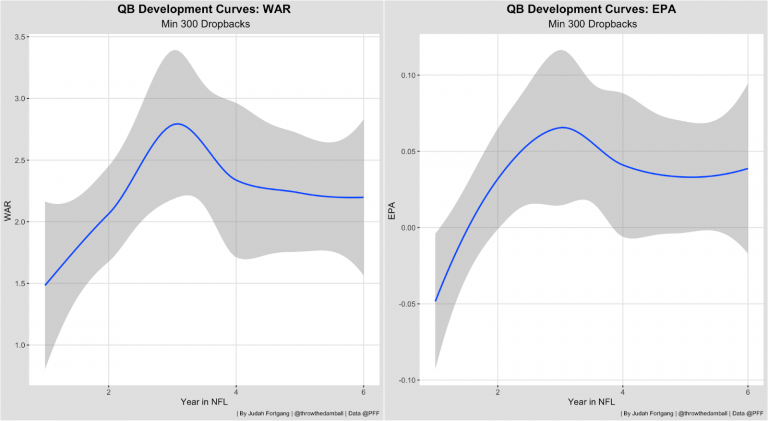

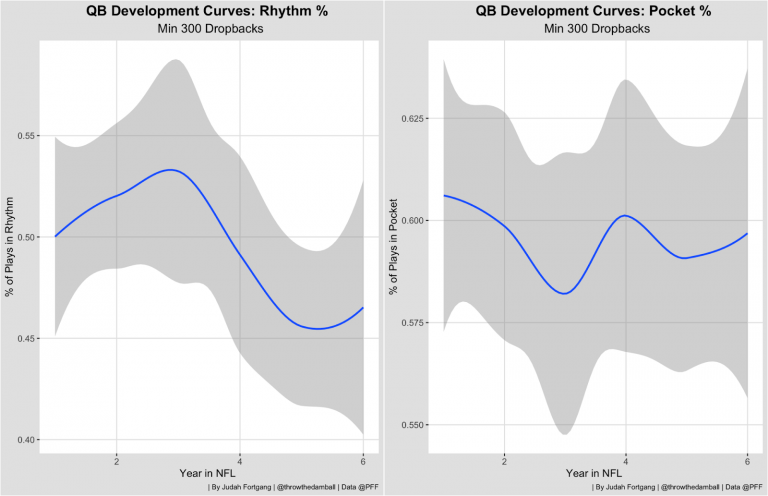

Let’s first establish some production metrics that show how quarterbacks improve in their production.

Using EPA and PFF WAR as our baseline, we can see that quarterback production improves as players gain more NFL experience. While a full exploration of this curve is for a different time, the key for us here is that we can see a clear and steep increase in production in both metrics from around Years 2-4 before it levels off. And once we start to tease out individual quarterback components in a similar manner, we can start to see the effective curve for each one of these stats.

This series of articles will take a slightly different route: Using PFF’s quarterback charting data as a foundation, we will explore the components of quarterback play — rhythm, accuracy, throw selection, progressions, decision-making and much more.

Through this exploration, we can hopefully learn more about the unique styles and skills of individual quarterbacks and the areas of the game and contexts in which they are more or less likely to succeed or fail. We can then apply those findings to better understand how components of quarterback skill sets interact with other players — for example, which quarterbacks would benefit from a good offensive line more than others? Which quarterback traits would best match with a dynamic after-the-catch receiver?

Lastly, by isolating specific traits, we can hopefully zero in on players whose traits allow them to deviate from the norm — for example, while quarterback play from a non-clean pocket is generally unstable, certain players, because of their traits, should be seen as outliers as opposed to noise.

This article will set the stage for an upcoming series on quarterback composites by focusing on, and answering, the following question: Which components of a quarterback's development lead to improvement? Put differently, we know that a quarterback is likely to increase their production from their first few NFL seasons to their next few seasons, but what part of their game develops the most?

Without looking at a signal-caller's production in specific areas (e.g., their expected points added across different situations such as play action or pressure), we will try to isolate broader attributes that lead to improved quarterback play. Do quarterbacks become more accurate? Improve their rhythm and timing? Improve their throw selection? Get better with progressions? Advance in their pocket awareness and escapability?

Let’s first establish some production metrics that show how quarterbacks improve in their production.

Using EPA and PFF WAR as our baseline, we can see that quarterback production improves as players gain more NFL experience. While a full exploration of this curve is for a different time, the key for us here is that we can see a clear and steep increase in production in both metrics from around Years 2-4 before it levels off. And once we start to tease out individual quarterback components in a similar manner, we can start to see the effective curve for each one of these stats.

The context of a receiver being open or covered is useful, and it also brings up some important confounding factors worth discussing. As we have seen in recent years, teams with quarterbacks on rookie deals have more ammunition to spend at receiver — think Stefon Diggs in 2020 and A.J. Brown and Tyreek Hill in 2022, among others — providing the quarterback with more open windows to throw to.

Framed differently, do quarterbacks really improve their throw selection, or do better circumstances elevate the base rates for success?

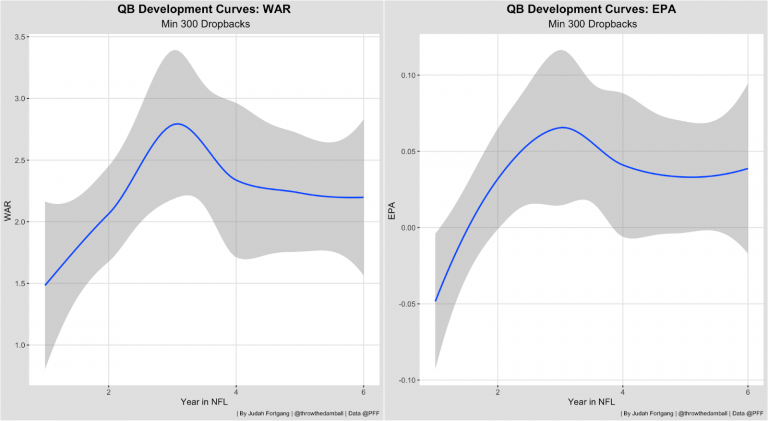

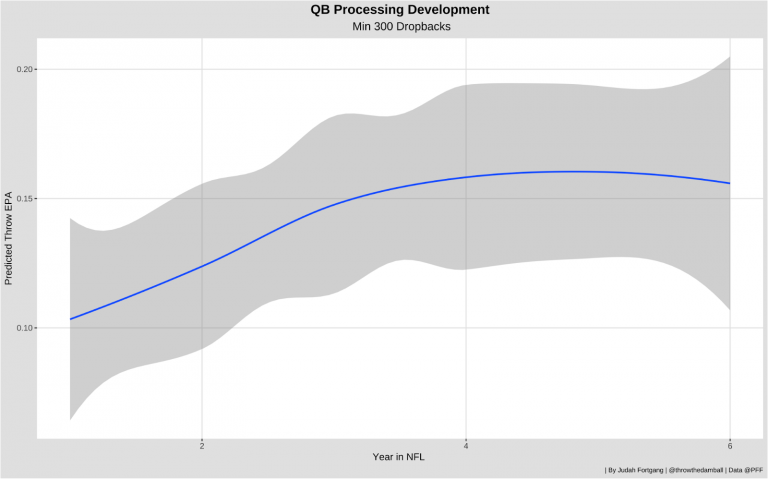

In the course of this research, I have also built a few metrics to evaluate quarterback processing and decision-making — of which a few future pieces will focus on — that would suggest a quarterback's processing, even adjusted for improved situations, gets better as they develop and follows a similar curve to throws to open receivers.

Saving the full note for later, this metric essentially predicts the expected EPA based on a quarterback's decision, given all his available route options and adjusted for expectation (e.g., having more open receivers). The curve, then, suggests a quarterback improves in their decision-making and throw selection even when we adjust for improved wide receiver play and surrounding talent.

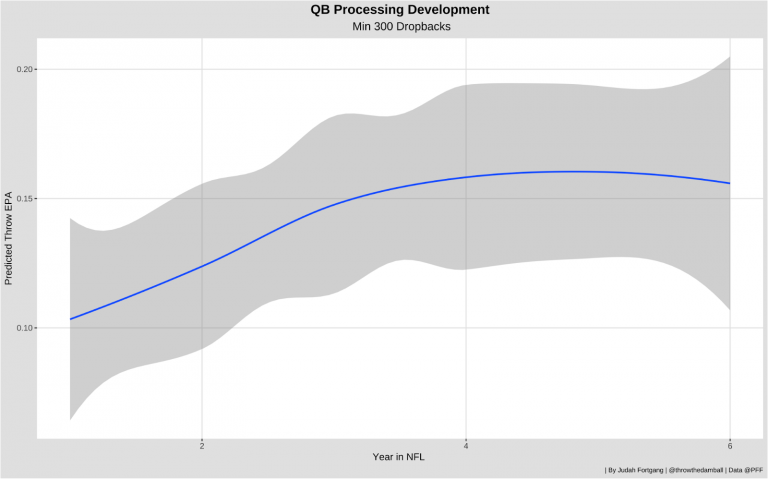

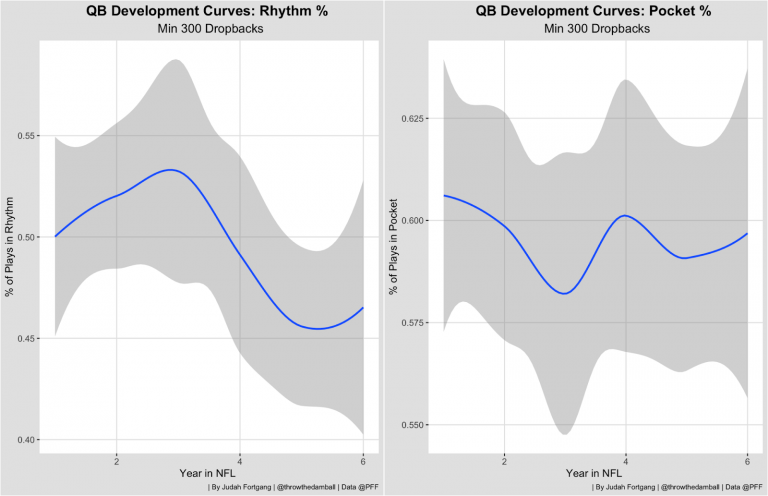

In the same vein as attempt selection, as quarterbacks adjust to the speed of the league, one might look at their play when in rhythm and from within the pocket to form a proxy for timing and ability to “play within structure.” And again, it is important to note the base rates for plays charted “in rhythm” and within the pocket.

To put these numbers in context, the difference between staying in the pocket and in rhythm and not is larger than the gap between the No. 1 and No. 32 offenses every year. But there is no real increase in the percentage of throws in rhythm or in the pocket for young quarterbacks.

The curves here suggest significant randomness, as players remain at similar stages in Year 1 and Year 4. This relationship for rhythm and pocket presence is similarly true with progressions, as improved play throughout progressions follows a noisy curve.

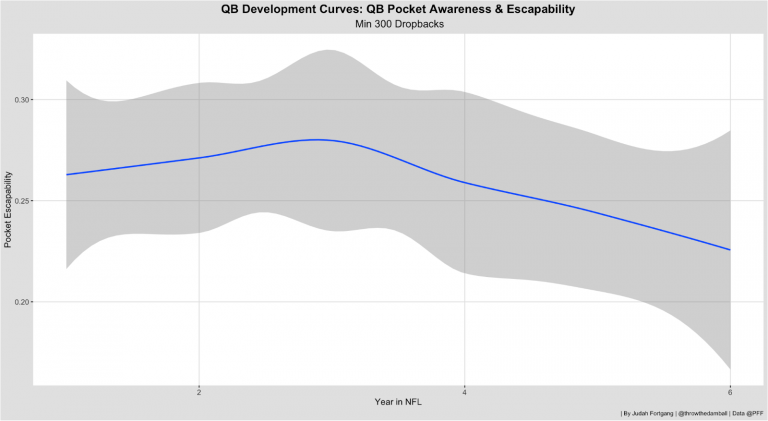

What about pocket awareness and escapability? We can use PFF charting to see how quarterbacks perform when they scramble outside of the pocket to avoid pressure — a base of -0.14 EPA — rather than stay in the pocket with pressure, which has a base rate of -0.33 EPA.

As with most curves we’ve seen, despite scrambling out of a messy pocket being a net positive, there is no real development for quarterbacks in this area. In a similar vein, quarterbacks do not seem to improve in their sack avoidance.

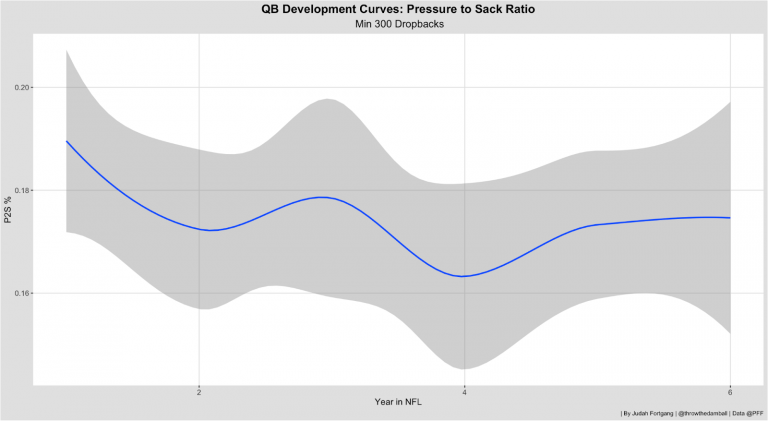

There is, again, a noisy curve for how often quarterback pressure turns into sacks.

Framed differently, do quarterbacks really improve their throw selection, or do better circumstances elevate the base rates for success?

In the course of this research, I have also built a few metrics to evaluate quarterback processing and decision-making — of which a few future pieces will focus on — that would suggest a quarterback's processing, even adjusted for improved situations, gets better as they develop and follows a similar curve to throws to open receivers.

Saving the full note for later, this metric essentially predicts the expected EPA based on a quarterback's decision, given all his available route options and adjusted for expectation (e.g., having more open receivers). The curve, then, suggests a quarterback improves in their decision-making and throw selection even when we adjust for improved wide receiver play and surrounding talent.

In the same vein as attempt selection, as quarterbacks adjust to the speed of the league, one might look at their play when in rhythm and from within the pocket to form a proxy for timing and ability to “play within structure.” And again, it is important to note the base rates for plays charted “in rhythm” and within the pocket.

Stat EPA In EPA Out

Pocket 0.21 -0.25

Rhythm 0.27 -0.25To put these numbers in context, the difference between staying in the pocket and in rhythm and not is larger than the gap between the No. 1 and No. 32 offenses every year. But there is no real increase in the percentage of throws in rhythm or in the pocket for young quarterbacks.

The curves here suggest significant randomness, as players remain at similar stages in Year 1 and Year 4. This relationship for rhythm and pocket presence is similarly true with progressions, as improved play throughout progressions follows a noisy curve.

What about pocket awareness and escapability? We can use PFF charting to see how quarterbacks perform when they scramble outside of the pocket to avoid pressure — a base of -0.14 EPA — rather than stay in the pocket with pressure, which has a base rate of -0.33 EPA.

As with most curves we’ve seen, despite scrambling out of a messy pocket being a net positive, there is no real development for quarterbacks in this area. In a similar vein, quarterbacks do not seem to improve in their sack avoidance.

There is, again, a noisy curve for how often quarterback pressure turns into sacks.

www.pff.com/news/nfl-data-study-components-quarterback-play-development

How to run an NFL franchise, Part II: Finding a legitimate No. 1 quarterback by Nick Baumgardner and Diante Lee

Your quarterback: Are there ‘must-have’ traits or deal-breakers? Who were some of your favorite top-100 and Day 3 QBs in recent drafts?

Nick Baumgardner: Physically, my parameters would equal what Diante mentions below (minimum 6 feet tall, 215 pounds). From a processing standpoint, if a QB struggles consistently with his feet versus pressure over multiple college seasons, I’m probably out early. If he struggles to make consistent, basic throws from a stable base in the pocket, I’m probably out. So much about mental processing is set in stone, and a football coach isn’t changing that.

However, the overall process of playing quarterback at a high level can be coached, taught and improved. Out-of-this-world tools — like those possessed by Anthony Richardson, Trey Lance, etc. — cannot. In terms of first-round QBs over the past five years, my preferred prospects at the time were Trevor Lawrence, Joe Burrow, Justin Fields, C.J. Stroud, Justin Herbert, Bryce Young and Richardson.

Burrow has outplayed them all, but I might have rated Lawrence higher if the two were in the same class. Lawrence’s true freshman campaign at Clemson was one of the best I’ve seen by a Power 5 starter, and college football looked easy for him by the end of his third year. I overlooked this, in part because his career started later, but Burrow had the best individual season — regardless of class — any QB has had this century. Like Lawrence, he was basically calling his shots on offense by the end.

In terms of Day 3 guys over the past five draft cycles, Bailey Zappe and Gardner Minshew were my two favorite high-floor prospects.

Diante Lee: I need to know what kind of pure dropback passer you are, whether you can punish a blitzing defense, and what kind of QB you turn into when facing pressure.

The average sizes and athletic traits of QBs have been trending closer to what we expect of other skill position players, so the idea of the tall and — for lack of a better term — “handsome” passer is a dying paradigm in the league, but size still matters. I would like to have a QB who’s at least a legitimate 6-0 and 215 pounds. NFL defenses averaged 92 combined sacks and QB knockdowns in 2022, so you need a body that can withstand the type of beating a backup running back would take.

In the last handful of drafts, that would have looked like Stroud, Richardson, Lawrence, Fields and Herbert — no surprise on this caliber of player. I may have pursued some of the mid-round guys like Will Levis, Desmond Ridder, Kellen Mond and Drew Lock as potential starters. Zappe, Sam Ehlinger and Brock Purdy are Day 3 guys I’d have been interested in as quality backups.

Nick Baumgardner: Physically, my parameters would equal what Diante mentions below (minimum 6 feet tall, 215 pounds). From a processing standpoint, if a QB struggles consistently with his feet versus pressure over multiple college seasons, I’m probably out early. If he struggles to make consistent, basic throws from a stable base in the pocket, I’m probably out. So much about mental processing is set in stone, and a football coach isn’t changing that.

However, the overall process of playing quarterback at a high level can be coached, taught and improved. Out-of-this-world tools — like those possessed by Anthony Richardson, Trey Lance, etc. — cannot. In terms of first-round QBs over the past five years, my preferred prospects at the time were Trevor Lawrence, Joe Burrow, Justin Fields, C.J. Stroud, Justin Herbert, Bryce Young and Richardson.

Burrow has outplayed them all, but I might have rated Lawrence higher if the two were in the same class. Lawrence’s true freshman campaign at Clemson was one of the best I’ve seen by a Power 5 starter, and college football looked easy for him by the end of his third year. I overlooked this, in part because his career started later, but Burrow had the best individual season — regardless of class — any QB has had this century. Like Lawrence, he was basically calling his shots on offense by the end.

In terms of Day 3 guys over the past five draft cycles, Bailey Zappe and Gardner Minshew were my two favorite high-floor prospects.

Diante Lee: I need to know what kind of pure dropback passer you are, whether you can punish a blitzing defense, and what kind of QB you turn into when facing pressure.

The average sizes and athletic traits of QBs have been trending closer to what we expect of other skill position players, so the idea of the tall and — for lack of a better term — “handsome” passer is a dying paradigm in the league, but size still matters. I would like to have a QB who’s at least a legitimate 6-0 and 215 pounds. NFL defenses averaged 92 combined sacks and QB knockdowns in 2022, so you need a body that can withstand the type of beating a backup running back would take.

In the last handful of drafts, that would have looked like Stroud, Richardson, Lawrence, Fields and Herbert — no surprise on this caliber of player. I may have pursued some of the mid-round guys like Will Levis, Desmond Ridder, Kellen Mond and Drew Lock as potential starters. Zappe, Sam Ehlinger and Brock Purdy are Day 3 guys I’d have been interested in as quality backups.

Are there QBs over the past few draft cycles you’d have avoided?

Baumgardner: Mac Jones is the first to come to mind, although in many ways I’ve been proven too harsh on him. I was able to see Jones’ terrific processing skills at Alabama, but it was harder to separate his ability to find a given route from how wide open DeVonta Smith or Jaylen Waddle was. Jones is not an impressive athlete, and he QB’d one of the most talented Alabama teams of the Nick Saban era, but he’s been better than I thought he’d be. I’m curious to see his next step.

Not to pick on the Crimson Tide here, but my other answer would be Tua Tagovailoa, another quarterback who has performed better than I’d have predicted on draft day. His injury concerns were real, and he was drafted during the spring of 2020 when the draft’s medical-testing process was tough because of the pandemic. I liked him as a first-round QB but not in the top five.

Lee: I would’ve passed on guys like Young, Tagovailoa and Kyler Murray. The size and play style of Young and Murray are genuine worries of mine. It’s hard to live in extend-and-create mode without elite arm talent in this league, especially if you don’t have the physical frame to shake off rushers. Tagovailoa has a quick release and diagnoses coverage pictures on the fly, but he’s not creating much outside of structure or beating tight coverage windows with his arm.

I do think there’s a world in which each of these players is a successful quarterback for a competitive team — we’ve already seen it from Tagovailoa and Murray. But the guardrails you’d need to get the most out of them often make you one-dimensional in the passing game, and one-dimensional passers are taken advantage of in big moments.

Baumgardner: Mac Jones is the first to come to mind, although in many ways I’ve been proven too harsh on him. I was able to see Jones’ terrific processing skills at Alabama, but it was harder to separate his ability to find a given route from how wide open DeVonta Smith or Jaylen Waddle was. Jones is not an impressive athlete, and he QB’d one of the most talented Alabama teams of the Nick Saban era, but he’s been better than I thought he’d be. I’m curious to see his next step.

Not to pick on the Crimson Tide here, but my other answer would be Tua Tagovailoa, another quarterback who has performed better than I’d have predicted on draft day. His injury concerns were real, and he was drafted during the spring of 2020 when the draft’s medical-testing process was tough because of the pandemic. I liked him as a first-round QB but not in the top five.

Lee: I would’ve passed on guys like Young, Tagovailoa and Kyler Murray. The size and play style of Young and Murray are genuine worries of mine. It’s hard to live in extend-and-create mode without elite arm talent in this league, especially if you don’t have the physical frame to shake off rushers. Tagovailoa has a quick release and diagnoses coverage pictures on the fly, but he’s not creating much outside of structure or beating tight coverage windows with his arm.

I do think there’s a world in which each of these players is a successful quarterback for a competitive team — we’ve already seen it from Tagovailoa and Murray. But the guardrails you’d need to get the most out of them often make you one-dimensional in the passing game, and one-dimensional passers are taken advantage of in big moments.

Roster decisions, especially those as important as choosing a QB, aren’t made by the GM alone. What traits would you be looking for in a director of player personnel? Which recent front-office regimes best reflect your approach?

Baumgardner: I need scouts who are capable of identifying the best player on the field, in any situation, before working back and stacking from there. If we can’t identify players at a granular level via film and game study, then we’re dead on arrival.

The data gathered from film and in-person scouting of college (heavy emphasis here) and pro prospects will drive the bus. Analytics will sit in the passenger seat and yell at the bus driver — and have the right to be heard in every decision we make. Analytics will always be embraced and respected. Still, it’s more important to me that the personnel director knows what “elite” looks like, what it doesn’t look like and every shade of gray in between.

Overall speed, which includes agility and explosiveness, will always be my most sought-after trait. However, if I have a 1a, it’s versatility. The ability to do more than one thing well is so valuable, not just from an in-game standpoint — as it helps with how you match up on offense and defense — but from a roster-construction standpoint, too.

On all of those notes, I can’t remember the last time I disagreed with a major decision the Ravens made. Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and San Francisco would be other favorites.

Lee: To give my head coach the tools he needs to build this thing properly, there has to be a layered approach. First, you have to identify which positions are premium and ensure those guys are at the top of your board. Then, almost more importantly, we’d need our scouting team to declare which role-player positions are of high value and which are not.

Analytics is a huge tool for me because you have to set thresholds on key production and athletic metrics. You’d need to have a method to find out which edge rushers are generating valuable pressure, which QBs handle pressure well, which corners can press and produce at the catch point, etc. I won’t belabor every detail, but you want that data on hand to cross-reference with film and firsthand experience (which are data points in their own right).

Beyond that, measurables are a huge deal in my evaluations. I’ve made mention of this before, but I have a difficult time getting behind smaller and/or slower guys, no matter how well they’ve produced in their college careers. The teams I associate with excellent scouting — Baltimore, Green Bay, New England, Pittsburgh, Seattle and San Francisco — covet big guys and/or elite movement traits. I’d be comfortable missing out on a potential game-changer because he didn’t meet our baselines on size and speed.

Baumgardner: I need scouts who are capable of identifying the best player on the field, in any situation, before working back and stacking from there. If we can’t identify players at a granular level via film and game study, then we’re dead on arrival.

The data gathered from film and in-person scouting of college (heavy emphasis here) and pro prospects will drive the bus. Analytics will sit in the passenger seat and yell at the bus driver — and have the right to be heard in every decision we make. Analytics will always be embraced and respected. Still, it’s more important to me that the personnel director knows what “elite” looks like, what it doesn’t look like and every shade of gray in between.

Overall speed, which includes agility and explosiveness, will always be my most sought-after trait. However, if I have a 1a, it’s versatility. The ability to do more than one thing well is so valuable, not just from an in-game standpoint — as it helps with how you match up on offense and defense — but from a roster-construction standpoint, too.

On all of those notes, I can’t remember the last time I disagreed with a major decision the Ravens made. Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and San Francisco would be other favorites.

Lee: To give my head coach the tools he needs to build this thing properly, there has to be a layered approach. First, you have to identify which positions are premium and ensure those guys are at the top of your board. Then, almost more importantly, we’d need our scouting team to declare which role-player positions are of high value and which are not.

Analytics is a huge tool for me because you have to set thresholds on key production and athletic metrics. You’d need to have a method to find out which edge rushers are generating valuable pressure, which QBs handle pressure well, which corners can press and produce at the catch point, etc. I won’t belabor every detail, but you want that data on hand to cross-reference with film and firsthand experience (which are data points in their own right).

Beyond that, measurables are a huge deal in my evaluations. I’ve made mention of this before, but I have a difficult time getting behind smaller and/or slower guys, no matter how well they’ve produced in their college careers. The teams I associate with excellent scouting — Baltimore, Green Bay, New England, Pittsburgh, Seattle and San Francisco — covet big guys and/or elite movement traits. I’d be comfortable missing out on a potential game-changer because he didn’t meet our baselines on size and speed.

theathletic.com/4699489/2023/07/21/nfl-ownership-franchise-quarterbacks/

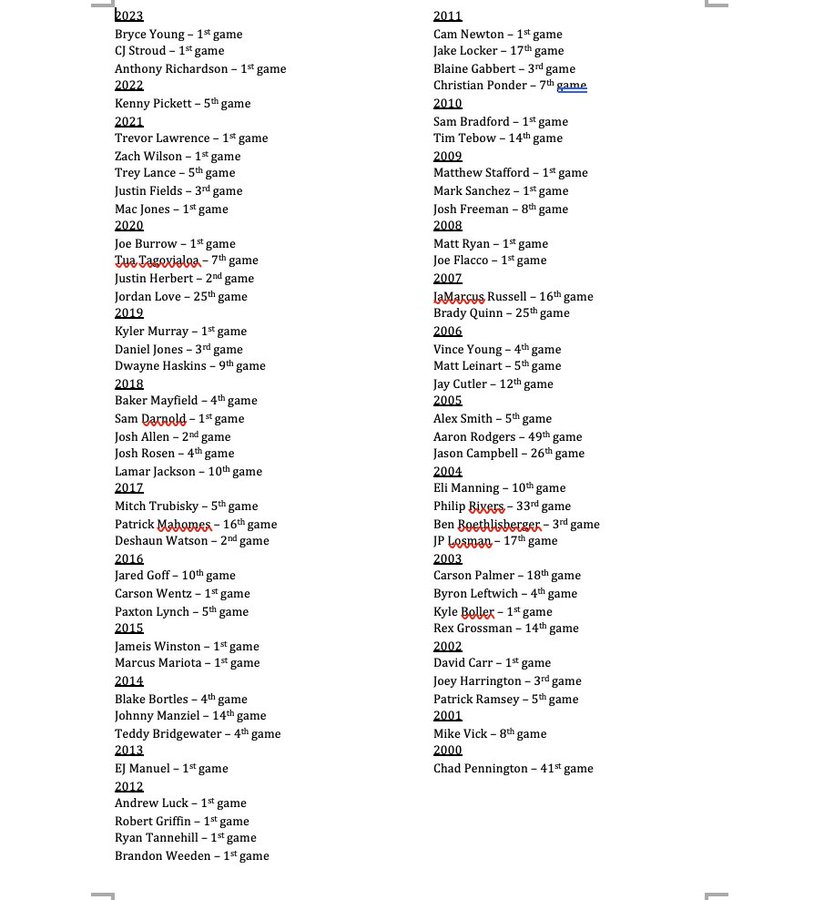

We Don’t Do a Great Job Talking About Starting or Sitting Rookie Quarterbacks by Arif Hasan

Can Quarterback History Guide the Sit-Start Decision?

Rodgers and Mahomes were behind Pro Bowl – or better – quarterbacks who had just made the playoffs. Maybe they would have started in different circumstances.

And what of the failures? We can’t say with any certainty that quarterbacks who followed either path but failed did so because they either sat or started. Would Tim Tebow have been a better quarterback if he could have spent time on the bench? Was Jake Locker a victim of starting too early, or was it merely injuries? Would Ryan Tannehill’s career arc be different if he had the luxury to sit in Miami?

We are essentially hunting for one kind of signal and ignoring another. It’s not really an acceptable data practice in most areas of life – if we were deciding between watching two movies, we wouldn’t make the choice solely because one of the actors was in absolutely more successful movies.

If we only made those choices based on the sheer number of successes, we’d be inclined to choose Nicolas Cage, who has been in more bad and good movies combined than possibly anyone – over Ryan Gosling, who has been in far fewer successful movies but has a much higher hit rate of critically acclaimed films.

That’s what these quarterback debates do – they count success and ignore the failures. There’s no ability to meaningfully generate a “rate” of success with either approach. There’s another signal mucking up the data, too – quarterbacks who sit are not very good.

We don’t know if Jordan Love had to wait to start because he needed time to develop, because he’s simply not any good or if it’s just because it’s kind of difficult to bench Aaron Rodgers. Any of those three non-mutually exclusive options could be the reason that Love wouldn’t become a starting quarterback until this year.

We can be reasonably confident that Paxton Lynch couldn’t win the gig because of a baseline lack of talent, but it’s harder to say that Geno Smith flamed out with the New York Jets because he wasn’t allowed to sit right away. Certainly, his extensive experience in the league as a backup is a reason he re-emerged in Seattle, but if he had bad coaching in New York, there may not be much sitting behind a veteran can do.

It may even be the case that someone like Carson Wentz could have benefited from sitting. He had a remarkable 2017, but the habits he needed to build to sustain that season weren’t a part of his playstyle in any permanent way. When he suffered setbacks, he reverted to those habits, including a tendency to hold the ball on too long and stare down receivers. We may say the same of Jared Goff.

The truth is that we don’t know. Instead of looking at success, failure and counterfactuals, we can break it down into component parts, which is what the Colts seemingly did.

Rodgers and Mahomes were behind Pro Bowl – or better – quarterbacks who had just made the playoffs. Maybe they would have started in different circumstances.

And what of the failures? We can’t say with any certainty that quarterbacks who followed either path but failed did so because they either sat or started. Would Tim Tebow have been a better quarterback if he could have spent time on the bench? Was Jake Locker a victim of starting too early, or was it merely injuries? Would Ryan Tannehill’s career arc be different if he had the luxury to sit in Miami?

We are essentially hunting for one kind of signal and ignoring another. It’s not really an acceptable data practice in most areas of life – if we were deciding between watching two movies, we wouldn’t make the choice solely because one of the actors was in absolutely more successful movies.

If we only made those choices based on the sheer number of successes, we’d be inclined to choose Nicolas Cage, who has been in more bad and good movies combined than possibly anyone – over Ryan Gosling, who has been in far fewer successful movies but has a much higher hit rate of critically acclaimed films.

That’s what these quarterback debates do – they count success and ignore the failures. There’s no ability to meaningfully generate a “rate” of success with either approach. There’s another signal mucking up the data, too – quarterbacks who sit are not very good.

We don’t know if Jordan Love had to wait to start because he needed time to develop, because he’s simply not any good or if it’s just because it’s kind of difficult to bench Aaron Rodgers. Any of those three non-mutually exclusive options could be the reason that Love wouldn’t become a starting quarterback until this year.

We can be reasonably confident that Paxton Lynch couldn’t win the gig because of a baseline lack of talent, but it’s harder to say that Geno Smith flamed out with the New York Jets because he wasn’t allowed to sit right away. Certainly, his extensive experience in the league as a backup is a reason he re-emerged in Seattle, but if he had bad coaching in New York, there may not be much sitting behind a veteran can do.

It may even be the case that someone like Carson Wentz could have benefited from sitting. He had a remarkable 2017, but the habits he needed to build to sustain that season weren’t a part of his playstyle in any permanent way. When he suffered setbacks, he reverted to those habits, including a tendency to hold the ball on too long and stare down receivers. We may say the same of Jared Goff.

The truth is that we don’t know. Instead of looking at success, failure and counterfactuals, we can break it down into component parts, which is what the Colts seemingly did.

Quarterback Mechanics Matter

One other reason, among many, to sit a quarterback might be to focus on fixing his mechanics. Mechanics are a notoriously difficult subject to talk about – there isn’t one “true” mechanical model to follow for the position, and different body types demand different kinetic chains.

“Standard” quarterback mechanics have changed substantially in just the last two decades, too. The advances made by private quarterback coaches – not all of them good, but many of them – have changed the process, with a focus on developing athletic quarterbacks in particular.

We know about Tom House, but private coaches like Will Hewlett and Dr. Tom Gormely, Danny Hernandez, Jeff Christensen, Quincy Avery and others have changed the approach.

But there are still core things to keep in mind. Every coach knows that power comes from the ground and that the kinetic chain starts with good footwork. Torque through the abs and rotation of the shoulder matters. Finding a way to keep one’s hips open but not loose is generally good.

Coaches used to want quarterbacks to keep the ball high, near the ear. But in the modern NFL, keeping the ball tight to the pec is preferred for a variety of reasons. And changing those deeply ingrained habits takes time – putting players without grounded practice in a new style of mechanics means they revert to old habits.

That might actually be one reason Rodgers had to sit. He kept the ball “on the shelf” near his ear, but it resulted in a robotic throwing motion. A few years later, he emerged as the starter in Green Bay with a much more efficient mechanical process.

Compare that to Tebow, who promised to work on his throwing motion every year and unveiled a more efficient process in camp before the season started. But when the bullets started flying, his mechanics would degrade and he’d revert to old habits.

When put back into the pressure cooker, mechanics that haven’t been solidified disappear.

In short, different skill deficits means different approaches to quarterback development.

One other reason, among many, to sit a quarterback might be to focus on fixing his mechanics. Mechanics are a notoriously difficult subject to talk about – there isn’t one “true” mechanical model to follow for the position, and different body types demand different kinetic chains.

“Standard” quarterback mechanics have changed substantially in just the last two decades, too. The advances made by private quarterback coaches – not all of them good, but many of them – have changed the process, with a focus on developing athletic quarterbacks in particular.

We know about Tom House, but private coaches like Will Hewlett and Dr. Tom Gormely, Danny Hernandez, Jeff Christensen, Quincy Avery and others have changed the approach.

But there are still core things to keep in mind. Every coach knows that power comes from the ground and that the kinetic chain starts with good footwork. Torque through the abs and rotation of the shoulder matters. Finding a way to keep one’s hips open but not loose is generally good.

Coaches used to want quarterbacks to keep the ball high, near the ear. But in the modern NFL, keeping the ball tight to the pec is preferred for a variety of reasons. And changing those deeply ingrained habits takes time – putting players without grounded practice in a new style of mechanics means they revert to old habits.

That might actually be one reason Rodgers had to sit. He kept the ball “on the shelf” near his ear, but it resulted in a robotic throwing motion. A few years later, he emerged as the starter in Green Bay with a much more efficient mechanical process.

Compare that to Tebow, who promised to work on his throwing motion every year and unveiled a more efficient process in camp before the season started. But when the bullets started flying, his mechanics would degrade and he’d revert to old habits.

When put back into the pressure cooker, mechanics that haven’t been solidified disappear.

In short, different skill deficits means different approaches to quarterback development.

wideleftpost.substack.com/p/we-dont-do-a-great-job-talking-about

Now that the Trey Lance fantasies are over, just wanted to highlight this informative post as well as share this tid:

... and neither is this Chris guy.

... and neither is this Chris guy.