Post by Purple Pain on May 22, 2020 14:58:23 GMT -6

PFF: The new NFL offense is an old NFL offense: How the 49ers, Titans, Vikings and others are evolving Mike Shanahan's offensive scheme

...

...

...

...

< FILM STUDY AND ANALYSIS AT LINK >

Rest at link:

www.pff.com/news/nfl-new-nfl-offense-49ers-titans-packers-mike-shanahan-offense

It’s finally happening. After years of living in the shadow of first the remnants of the West Coast offense and then the new spread offenses of the 2000s, the Mike Shanahan/Gary Kubiak/Alex Gibbs offense is finally making a breakthrough.

This particular offensive scheme coalesced in 1997, just in time for the Denver Broncos to win back-to-back Super Bowl championships. Skip forward two decades, and Mike Shanahan’s coaching tree is finally starting to blossom. Sean McVay and Kyle Shanahan both developed under Mike Shanahan in their years together in Washington before becoming head coaches. And now, after the success of McVay in Los Angeles and Shanahan The Younger in San Francisco, the rest of the league is trying to find success by hiring their underlings.

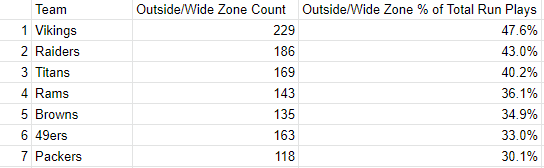

It’s about time. The system, built on the “wide zone” play, has always produced greater results than the sum of the parts involved would indicate, but its spread never took off, even after the 1997 and 1998 Super Bowl wins. It has now, though. In fact, six of the top seven teams in terms of outside- or wide-zone percentage in 2019 have connections to Mike Shanahan.

A season ago, the Minnesota Vikings brought in Gary Kubiak — Mike Shanahan’s quarterbacks’ coach in Denver — to help Kevin Stefanski run the offense. Arthur Smith, the Tennessee Titans’ offensive coordinator, spent a year under Matt Lafleur. The Raiders’ offensive line coach is Tom Cable, who spent a season coaching the Atlanta Falcons’ offensive line in 2006 with Alex Gibbs, who was Mike Shanahan’s offensive line coach with the Broncos. The Los Angeles Rams are coached by Sean McVay, who was Mike Shanahan’s tight ends coach in Washington. The San Francisco 49ers are led by Kyle Shanahan, who, at one point, was just a twinkle in Mike Shanahan’s eye. The Packers are coached by the aforementioned Matt Lafleur, who was Sean McVay’s offensive coordinator in Los Angeles and worked under both Shanahans — it’s the seven degrees of wide zone.

And those seven teams accounted for 37% of the outside zone runs in the NFL in 2019.

We’ve finally got to the point where this system is becoming sought after in the NFL. You would have thought after the success of the Broncos in the late 90s that the same blossoming would have occurred, but it didn’t, at least not to the degree that we’ve already seen in the 2010s. The originators of the scheme found their way together in 1995 on Mike Shanahan’s first Broncos staff, and they stayed together until 2003 when Gibbs would go run the system in Atlanta. Kubiak would only leave to become the head coach of the Houston Texans in 2006.

The three coaches spent nine years together in total, so the dissemination of the scheme took a while to spread across the league. And by that point, it might have been old news. It’s not that teams hadn’t been running outside zone — or as they call it, “wide zone” — but the use of it as the focal point of the offense, especially from a single-back set, was contained to this particular coaching tree.

There is a good chance, in the coming years, that if your favorite football team has a coaching vacancy and wants to hire an offensive-minded coach, he could be coming off the “wide zone” coaching tree.

To understand how this offense works, we have to go all the way back to Mike Shanahan’s younger days. We start in 1986...

This particular offensive scheme coalesced in 1997, just in time for the Denver Broncos to win back-to-back Super Bowl championships. Skip forward two decades, and Mike Shanahan’s coaching tree is finally starting to blossom. Sean McVay and Kyle Shanahan both developed under Mike Shanahan in their years together in Washington before becoming head coaches. And now, after the success of McVay in Los Angeles and Shanahan The Younger in San Francisco, the rest of the league is trying to find success by hiring their underlings.

It’s about time. The system, built on the “wide zone” play, has always produced greater results than the sum of the parts involved would indicate, but its spread never took off, even after the 1997 and 1998 Super Bowl wins. It has now, though. In fact, six of the top seven teams in terms of outside- or wide-zone percentage in 2019 have connections to Mike Shanahan.

A season ago, the Minnesota Vikings brought in Gary Kubiak — Mike Shanahan’s quarterbacks’ coach in Denver — to help Kevin Stefanski run the offense. Arthur Smith, the Tennessee Titans’ offensive coordinator, spent a year under Matt Lafleur. The Raiders’ offensive line coach is Tom Cable, who spent a season coaching the Atlanta Falcons’ offensive line in 2006 with Alex Gibbs, who was Mike Shanahan’s offensive line coach with the Broncos. The Los Angeles Rams are coached by Sean McVay, who was Mike Shanahan’s tight ends coach in Washington. The San Francisco 49ers are led by Kyle Shanahan, who, at one point, was just a twinkle in Mike Shanahan’s eye. The Packers are coached by the aforementioned Matt Lafleur, who was Sean McVay’s offensive coordinator in Los Angeles and worked under both Shanahans — it’s the seven degrees of wide zone.

And those seven teams accounted for 37% of the outside zone runs in the NFL in 2019.

We’ve finally got to the point where this system is becoming sought after in the NFL. You would have thought after the success of the Broncos in the late 90s that the same blossoming would have occurred, but it didn’t, at least not to the degree that we’ve already seen in the 2010s. The originators of the scheme found their way together in 1995 on Mike Shanahan’s first Broncos staff, and they stayed together until 2003 when Gibbs would go run the system in Atlanta. Kubiak would only leave to become the head coach of the Houston Texans in 2006.

The three coaches spent nine years together in total, so the dissemination of the scheme took a while to spread across the league. And by that point, it might have been old news. It’s not that teams hadn’t been running outside zone — or as they call it, “wide zone” — but the use of it as the focal point of the offense, especially from a single-back set, was contained to this particular coaching tree.

There is a good chance, in the coming years, that if your favorite football team has a coaching vacancy and wants to hire an offensive-minded coach, he could be coming off the “wide zone” coaching tree.

To understand how this offense works, we have to go all the way back to Mike Shanahan’s younger days. We start in 1986...

The rest is history. The Broncos won back-to-back Super Bowls and Shanahan posted an incredible 138 wins and only 86 losses as head coach for the team. And most of those wins came after John Elway retired.

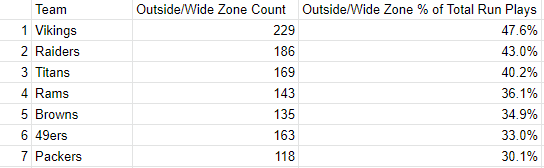

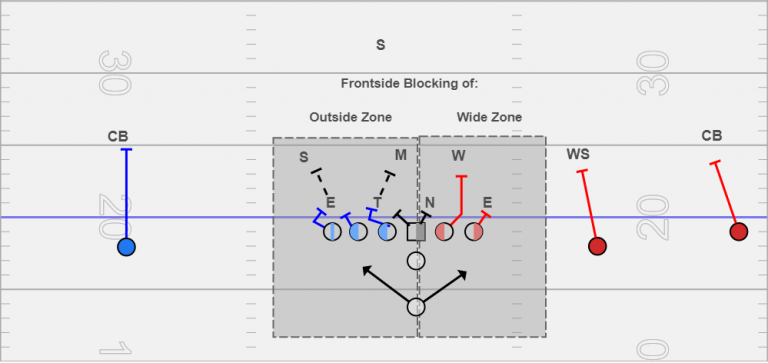

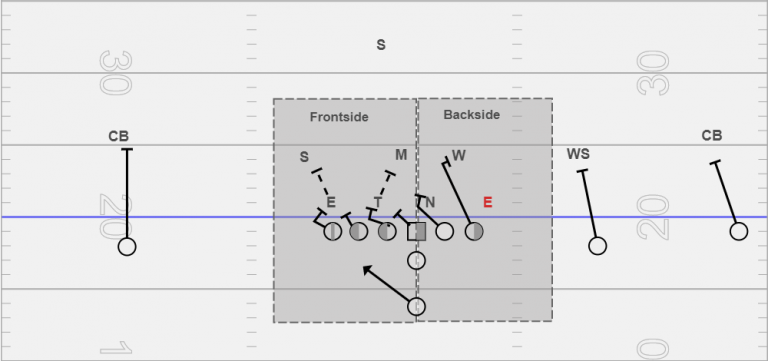

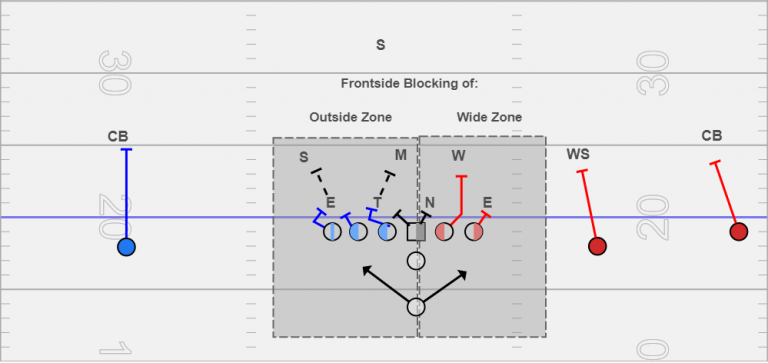

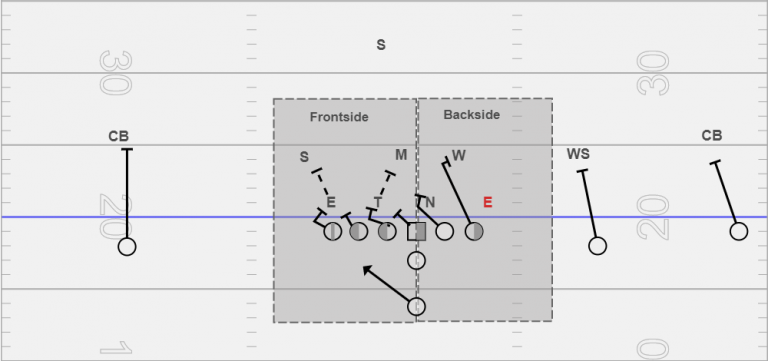

The wide zone and outside zone are both horizontal run plays that try to stretch the defense enough to find a vertical running seam. They differentiate themselves in that in the outside zone, the frontside offensive linemen are generally trying to “reach” or “hook” the playside defensive linemen to the side of the run direction. This allows the running back to get around to the outside, if possible. The wide zone tells the offensive linemen that rather than trying to get to the other side of the defensive linemen, we will just run and push them out the way.

On the backside, both systems are similar. The offensive linemen are at an angle disadvantage, so their job is to run hard and get in front of the backside defensive linemen and cut them off. The furthest backside defensive linemen is not blocked.

Stretching the frontside and cutting the backside gives the running back a lane for a potentially big gain.

The read for the running back on wide zone is a very binary decision tree: if the first player outside the tight end or tackle stays outside the block, he cuts in. If he works inside, he stays on his outside path. If the next defensive lineman stays outside the block, he keeps cutting in. If that player comes inside, he finds the crease right there.

The idea is that if the running back makes the right reads, he should not be tackled in the backfield. Where this play generally hits for big yards is when the running back cuts all the way back.

Listen to the commentators talk about how, in 1997, the new addition to the Broncos offense was allowing the running back the ability to cutback:

From 1997 to 2003 — when the three coaches were together — the Broncos finished top-five in the NFL in both overall yards per play and yards per rush attempt in four of those seven years. Gibbs then moved to Atlanta for the 2004 season, and the Falcons subsequently led the league in rushing yards per attempt in each of the following three seasons. Kubiak then became head coach of the Houston Texans in 2006, found running back Arian Foster in 2009, and then went on to finish third in rushing yards per attempt in 2010.

A decade later, the tree grows. Kyle Shanahan just went to the Super Bowl, Sean McVay is a year removed from going to the Super Bowl, Gary Kubiak is an offensive coordinator in Minnesota and former Vikings offensive coordinator Kevin Stefanski is now the head man in Cleveland. Green Bay has Matt Lafleur and Tennessee has Arthur Smith, who learned from Lafleur. Zac Taylor heads the Cincinnati Bengals and was once a part of Sean McVay’s staff.

The offense has stayed remarkably consistent after all these years. Elements of the modern game have found their way into the philosophy, but the core tenet — basing everything around wide zone — has stayed the same.

For this study, these are the data sets we are going to look at:

Cincinnati Bengals — 2019

Green Bay Packers — 2019

Tennessee Titans — 2019

Minnesota Vikings — 2019

San Francisco 49ers — 2017-19

Los Angeles Rams — 2017-19

The offense starts with that horizontal-stretching wide-zone play, which we chart as outside zone. This concept is really made for an under-center quarterback (or at least pistol, as we see in college a lot). By being under center, it allows the running to start on a downfield track immediately. In an offset-shotgun look, the running back has to come across the quarterback’s face with his shoulders turned to the sideline, making it harder to cut back.

The league average for teams going under center on first and second down over the last three seasons is 54.1%, but our wide-zone teams show significantly more of those under-center looks.

The wide zone and outside zone are both horizontal run plays that try to stretch the defense enough to find a vertical running seam. They differentiate themselves in that in the outside zone, the frontside offensive linemen are generally trying to “reach” or “hook” the playside defensive linemen to the side of the run direction. This allows the running back to get around to the outside, if possible. The wide zone tells the offensive linemen that rather than trying to get to the other side of the defensive linemen, we will just run and push them out the way.

On the backside, both systems are similar. The offensive linemen are at an angle disadvantage, so their job is to run hard and get in front of the backside defensive linemen and cut them off. The furthest backside defensive linemen is not blocked.

Stretching the frontside and cutting the backside gives the running back a lane for a potentially big gain.

The read for the running back on wide zone is a very binary decision tree: if the first player outside the tight end or tackle stays outside the block, he cuts in. If he works inside, he stays on his outside path. If the next defensive lineman stays outside the block, he keeps cutting in. If that player comes inside, he finds the crease right there.

The idea is that if the running back makes the right reads, he should not be tackled in the backfield. Where this play generally hits for big yards is when the running back cuts all the way back.

Listen to the commentators talk about how, in 1997, the new addition to the Broncos offense was allowing the running back the ability to cutback:

From 1997 to 2003 — when the three coaches were together — the Broncos finished top-five in the NFL in both overall yards per play and yards per rush attempt in four of those seven years. Gibbs then moved to Atlanta for the 2004 season, and the Falcons subsequently led the league in rushing yards per attempt in each of the following three seasons. Kubiak then became head coach of the Houston Texans in 2006, found running back Arian Foster in 2009, and then went on to finish third in rushing yards per attempt in 2010.

A decade later, the tree grows. Kyle Shanahan just went to the Super Bowl, Sean McVay is a year removed from going to the Super Bowl, Gary Kubiak is an offensive coordinator in Minnesota and former Vikings offensive coordinator Kevin Stefanski is now the head man in Cleveland. Green Bay has Matt Lafleur and Tennessee has Arthur Smith, who learned from Lafleur. Zac Taylor heads the Cincinnati Bengals and was once a part of Sean McVay’s staff.

The offense has stayed remarkably consistent after all these years. Elements of the modern game have found their way into the philosophy, but the core tenet — basing everything around wide zone — has stayed the same.

For this study, these are the data sets we are going to look at:

Cincinnati Bengals — 2019

Green Bay Packers — 2019

Tennessee Titans — 2019

Minnesota Vikings — 2019

San Francisco 49ers — 2017-19

Los Angeles Rams — 2017-19

The offense starts with that horizontal-stretching wide-zone play, which we chart as outside zone. This concept is really made for an under-center quarterback (or at least pistol, as we see in college a lot). By being under center, it allows the running to start on a downfield track immediately. In an offset-shotgun look, the running back has to come across the quarterback’s face with his shoulders turned to the sideline, making it harder to cut back.

The league average for teams going under center on first and second down over the last three seasons is 54.1%, but our wide-zone teams show significantly more of those under-center looks.

Team Season % of 1st- and 2nd-down plays with QB under center

Vikings 2019 81.6%

Rams 2017-19 68.4%

49ers 2017-19 66.5%

Titans 2019 62.0%

Packers 2019 47.9%

Bengals 2019 38.3%

NFL Average 2017-19 54.1%...

Speaking of tailoring your offense to your personnel, let’s look at the players these coaches want on the field to run their wide-zone play. The Titans ran most of their wide-zone snaps (91 snaps) in 12 personnel (one running back, two tight ends) followed by 11 personnel (49) on early downs. The Packers were mostly 12 personnel, as well (50), though they also used 11 personnel (43). The Bengals ran it out of 11 personnel almost exclusively (50), which makes sense since Taylor came from McVay’s camp. The Rams ran 11-personnel wide zone 377 times in three years compared to 12-personnel wide zone only 89 times. Kyle Shanahan and Kubiak, on the other hand, preferred to have a fullback on the field, as their teams trotted out 21 personnel most of the time while running wide zone — 249 times in three years for the 49ers and 63 times last season for the Vikings.

That’s how adaptable the scheme is. You can put your best players on the field and still find a way to run it. Kyle Shanahan has Kyle Juszczyk, PFF’s second-highest-graded fullback over the last three seasons; the Vikings have C.J. Ham, who was the sixth-highest graded player at the position in 2019.

“Formationally” speaking, the concept only really works with a tight end at the core of the formation. Of the 1,640 wide-zone runs on early downs in this data set, fewer than 100 were in a “four-open formation,” either tips or doubles.

The differences between these teams come back to whether they have a fullback on the field or not — Shanahan and Kubiak have brought the fullback back into the mix; the other guys have kept true to their single-back formation.

The main component that the formation needs to have is the ability to go to the weakside or the strong side of the defense, regardless of formation.

The teams that live in 12 personnel have an easy way to do it because you can put a tight end on either side of the formation. The teams that prefer to use a fullback can put a tight end to one side and then use the fullback as the extra blocker to the other side

That’s how adaptable the scheme is. You can put your best players on the field and still find a way to run it. Kyle Shanahan has Kyle Juszczyk, PFF’s second-highest-graded fullback over the last three seasons; the Vikings have C.J. Ham, who was the sixth-highest graded player at the position in 2019.

“Formationally” speaking, the concept only really works with a tight end at the core of the formation. Of the 1,640 wide-zone runs on early downs in this data set, fewer than 100 were in a “four-open formation,” either tips or doubles.

The differences between these teams come back to whether they have a fullback on the field or not — Shanahan and Kubiak have brought the fullback back into the mix; the other guys have kept true to their single-back formation.

The main component that the formation needs to have is the ability to go to the weakside or the strong side of the defense, regardless of formation.

The teams that live in 12 personnel have an easy way to do it because you can put a tight end on either side of the formation. The teams that prefer to use a fullback can put a tight end to one side and then use the fullback as the extra blocker to the other side

...

Play-action dropbacks that used the wide-zone scheme action in 2019 is where the offense really shines. Every team but the lowly Bengals (turns out scheme can only go so far) saw a huge increase in their EPA per play mark on play-action passes that were run with the wide-zone action. The Titans and 49ers jumped out of the stratosphere, putting up 0.589 and 0.569 EPA per play, respectively; the Rams, Vikings and Packers followed with respective figures of 0.167, 0.152 and 0.109.

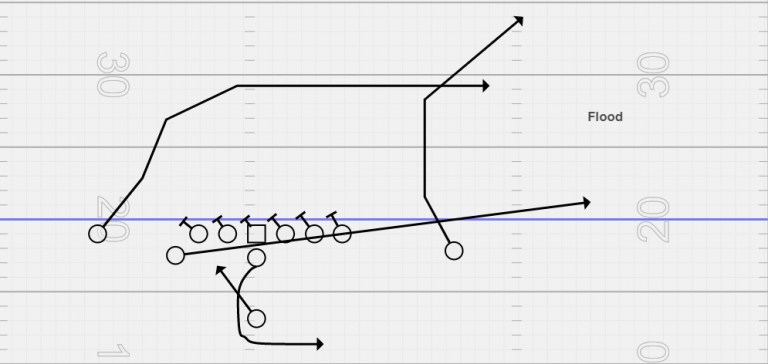

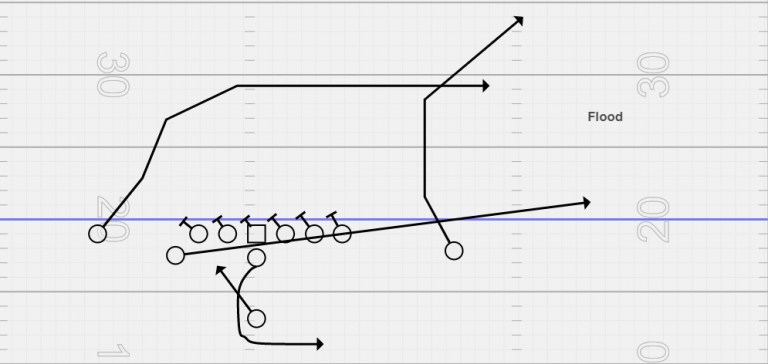

While each play-caller can get as creative as he wants when drawing up the pass concepts for the play action, there is at least one base concept that all of them use time and time again — the flood concept.

While each play-caller can get as creative as he wants when drawing up the pass concepts for the play action, there is at least one base concept that all of them use time and time again — the flood concept.

< FILM STUDY AND ANALYSIS AT LINK >

This offense gives you so much to deal with, and the concepts outlined here are just the tip of the iceberg.

Why an offense like this hasn’t spread is beyond me — it’s created stars out of Jimmy Garoppolo and Jared Goff, who might not be more than just average quarterbacks. Jimmy G brought the 49ers to the Super Bowl while being our 19th highest-graded passer in the regular season on non-play action dropbacks. Jared Goff was 17th in the same category when the Rams made the Super Bowl after the 2018 season.

The offense also helped reinvigorate Ryan Tannehill’s career, and we have also seen Matt Schaub, an average quarterback himself, propped up by playing for Gary Kubiak in Houston. It does beg the question of how much this helped John Elway finish his career as a back-to-back Super Bowl winner and become a sure-fire Hall of Famer and one of the NFL’s 100 greatest players.

While the West Coast offense needs an elite dropback passer and the new spread teams need an elite runner at quarterback, the wide zone scheme seems to prop up whoever is playing pivot for them.

I’m excited to see it’s evolved use over the next few years.

Why an offense like this hasn’t spread is beyond me — it’s created stars out of Jimmy Garoppolo and Jared Goff, who might not be more than just average quarterbacks. Jimmy G brought the 49ers to the Super Bowl while being our 19th highest-graded passer in the regular season on non-play action dropbacks. Jared Goff was 17th in the same category when the Rams made the Super Bowl after the 2018 season.

The offense also helped reinvigorate Ryan Tannehill’s career, and we have also seen Matt Schaub, an average quarterback himself, propped up by playing for Gary Kubiak in Houston. It does beg the question of how much this helped John Elway finish his career as a back-to-back Super Bowl winner and become a sure-fire Hall of Famer and one of the NFL’s 100 greatest players.

While the West Coast offense needs an elite dropback passer and the new spread teams need an elite runner at quarterback, the wide zone scheme seems to prop up whoever is playing pivot for them.

I’m excited to see it’s evolved use over the next few years.

Rest at link:

www.pff.com/news/nfl-new-nfl-offense-49ers-titans-packers-mike-shanahan-offense

... and neither is this Chris guy.

... and neither is this Chris guy.